Introduction

This is a collection of essays on finance, economics, philosophy, and public policy.

I’m passionate about learning how the philosophic and economic decisions made by businesses ultimately affect society, as well as how policy can influence these decisions for good and for ill. It is in search of answers related to these relationships that I began my vocational endeavors. Looking ahead, I want to continue to research and learn, hone my undergraduate thesis written on the morality of the corporation, and research policy surrounding the private equity firm.

The name of this website is intended to be ironic. Utopian and capitalistic societies are generally not considered to co-exist alongside one another. Thomas More notes this in his 1516 text utopia, and Joseph Schumpeter alludes to it in his text Socialism, Capitalism, and Democracy. For More, utopia (meaning “There is no such place”) is intended to show the ridiculousness of what society might look like without the so-called constraints of capitalism. In Utopia, luxury is unnecessary and monarchs avoid extravagance. Schumpeter believes capitalism to be evil at times, and yet it remains necessary to the development. “Creative destruction” is the term he famously uses to describe how capitalism forces markets to constantly adapt and reinvigorate with new momentum and freshly espoused ideas. Markets today are following this approach, but there has been an increasing emphasis by states to monitor and/or manage wealth.

In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission, a regulatory agency, does this by requiring publicly traded firms to release quarterly financial statements alongside an annually audited report. However, publicly traded firms do not account for more than half of the entire (public and private) market value in the United States. The New York Times noted in November 2015 that “the number of companies listed on the US stock exchange has decreased by 35% from 1995”, according to data from Weild & Company. Now, part of this trend may be due to the consolidation of the market. However, the macro trend points toward an increasing desire for companies to retreat to privacy. There are recent macroeconomic trends that have aided such an advance.

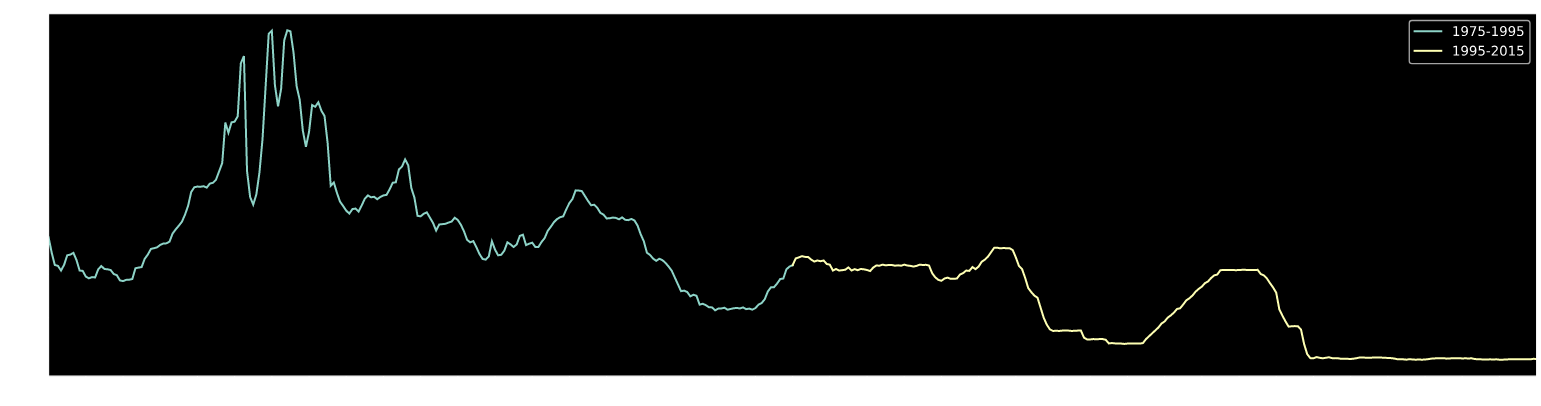

First, it is helpful to consider the interest rate decline in those 20 years between 1995 and 2015. In comparison to previous periods, the interest rate was remarkably low. Consider that between 1975 and 1995, the average interbank lending rate was 7.98%, while between 1995 and 2015 it was 2.60%- a 5.38% or 67% decrease in interest rate.

What this means is that it has become historically affordable for companies to borrow money, and this has led to a competitive private industry. Private Equity companies, brought to prominence in the 1980s and made famous through movies such as Barbarians at the Gate, work by purchasing a large stake (often majority) of a company and then leveraging it with debt, as this grows the enterprise value of the company more efficiently than other models. Future posts will describe why this is the case. In my industry experience, I have regularly worked with or had co-workers who consulted with companies essentially traded from one private equity client to another. By remaining private rather than going public, companies are able to return value to stakeholders by focusing on long-term rather than short-term goals (public pressures often necessitate earnings forecasts, for example).

Second, the size of the private market has grown dramatically since 1995. (https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/private%20equity%20and%20principal%20investors/our%20insights/the%20rise%20and%20rise%20of%20private%20equity/the-rise-and-rise-of-private-markets-mckinsey-global-private-markets-review-2018.ashx “McKinsey analysis”) shows private markets fundraising increasing from >$140B to $750B in 2017, a 540% increase in size. This has strengthened the credibility of the private markets, and banks have been increasingly looking to fund private ventures, particularly through venture capital arms. Perhaps the most obvious indicator of this is number of mega-unicorns (A “Unicorn” is a company valued >$1 billion). Companies like Uber ($68B), Airbnb ($29B), Xiamoi ($46B), and SpaceX ($21.5B) have all been highly publicized.

It should be noted that unicorns like Spotify ($30B) and Snap ($17B) have broached the public market in the past two years, perhaps indicating a trend of companies beginning to look for equity funding in their enterprises. However, this is not likely to slow the growth of private equity firms thirsty for leveraged capital. It is in the wake of this that I desire to explore questions of finance, economics, philosophy, and policy.